A personal fan site dedicated to the spiritual, political, philosophical, and radical interpretation of U2's music, lyrics, activism, and more. With head and heart connected to the white flag of peace, let's discuss how to get to the higher ground of "One Tree Hill" just outside the "City of Blinding Lights," "Where the Streets Have No Name" and freedom has the scent like the top of my newborn baby's head.

Of course, he's like me when he's against the war, but not when he's praising Condy Rice or Billy Graham--which is enough for "the right" to claim him as theirs.

After

We're all "One," just not the same.

And of course, Bono loves to make the links and loathes the divisions he sees between us—the real and imagined trenches between right and left, fundamentalist and free thinker, soldier and protester, preacher and punk. When Bono introduced "Sunday Bloody Sunday" by saying, "

Rather, I think he spoke to the war within, the divisions in our country since the culture war intensified, in our school and church communities, about dogmas and social demons, over drugs and religion, in our blurred and fatigued attitudes towards the war in Iraq, in our treatment of others with whom we disagree, including those we saw in the seats at this very show. With a "tough-guy" preteen onstage with him, Bono in his "coexist" bandanna offered his prayer for the next generation, "That in order to defeat a monster, we don't become a monster."

One more addendum: that last quote seems clearly a paraphrase of another radical thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche.

He said: "He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you."

Of course, I have always tried to remind myself of this in another context: when I rebel against the stagnant status quo, I do not want to become the stagnant status quo. Bono, I think, uses this as challenge for Europeans and Americans in the so-called War on Terror. In both cases, may we not become monsters. And as we intend, may it be so.

Imagine a love affair that lasts longer than a marriage—22 years! Since age 16, I’ve been driven by this passion, and even after absences that could last years, I always come back for more.

My magical and mystical object of affection is not a lover at all—but a band. Even though I like to call Bono “my boyfriend,” we’ve only met briefly before and after shows, with me in my fan’s capacity, one of the many.

A child of the first MTV generation, I wore out my dubbed copy of the Red Rocks show. My primal attraction to the white flag of Christian pacifist radicalism matched only by what this man’s voice does to my soul.

Of course, over the years, Bono Hewson would at times confuse the Christ within with his own messianic charisma. But this intense ego and eager magnetism were not the result of his massive fame—but rather the reasons for it.

As an anomaly within the punk-new wave underground, U2 shunned the fashion statements for an even more pretentious anti-fashion statement. On the late spring US leg of the War tour, U2 did gigs on college campuses. When Bono climbed the scaffolding or did a stage dive from the speaker stacks into the balcony, his reckless intensity infected U2’s growing fan base. He played for 200 or 2000 then with the riveting abandon he offers arenas and stadiums today, which of course inspires critics to cheer that he transformed a basketball hall into a basement gig.

When he boasted in Rolling Stone that U2 would be one the important bands, like the Beatles or the Who, people scoffed. I remember believing Bono, sharing the quote with a friend, and getting laughed at.

The only thing I should laugh at now is my obsession!

At 38, we’re packing the whole family into a car for a rock and roll road trip. I’m talking Mom and Dad (both a young 65), my wife, and my 16-year-old stepson. Because we share a fascination with the convergence of theology, politics, and pop culture charisma, yes. But really, for me, this is an emotional pilgrimage as much as anything.

Because these are songs about the love that hold us together and tear us about. The intimate family and the infinite family.

Bono’s latest love songs are family songs, with a universal specificity and a special universalism that brings tears to a middle-aged man as if he were a teenage girl.

We know Bono wrote this for dad, but it also describes my relationship with my partner of six years (who is also my wife of three).

You don’t have to go it alone

And it’s you when I look in the mirror

And it’s you when I don’t pick up the phone

We fight all the time

You and I

That’s alright

We’re the same soul

I don’t need to hear you say

If we weren’t so alike

You’d like me a whole lot more

I’ve been looking forward to sharing this with my family live since I learned of Vertigo 2005. Tonight, at the first of my two “family” shows, I finally will do just that.

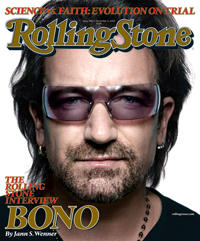

With considerable effort, I picked up the new Rolling Stone today. After a long detour and a delayed arrival at work, I have it to study and examine. The first store I visited still had the Paul McCartney cover. They had a different magazine called Ode with Bono on the cover, but the interview was only an excerpt from the Michka Assayas In Conversation book.

Although I've only begun to read, chewing on a section like a sweet I want to linger, Bono has soothed some of my political cynicism, showing his heart where I'd hoped it would be, streetwise and sensitive and sensibly self-aware.

And the Bono I feared had begun an inside associate of BushCo. seems missing when the Bono I thought I knew begins to speak: "But some people don't want America World Police. By the way, it might be cheaper to make friends out of potential enemies than to defend against them later."

I just ripped out the obnoxious car centerfold, and now Bono has the centerfold. Bono is "sick of Bono." Bono doesn't travel with security. Bono has Ali, and they both have my heart with the picture on page 67.

"An interesting story that someone told me once is that in Belfast, by what street someone lives on, you can tell not only their religion but tell how much money they’re making -- literally by which side of the road they live on, because the further up the hill, the more expensive the houses become. You can almost tell what the people are earning by the name of the street they live on and what side of that street they live on. That said something to me, and so I started writing about a place where the streets have no name...." -Bono

“Where the Streets Have No Name” is a rock hymn that suggests an imagined city. Originally conceived in contrast to what Bono knew of the brutal economic boundaries of an embattled Belfast and like the placeless place in John Lennon’s “Imagine,” Bono’s new world is beyond the borders of politics and imagination.

Bono’s words summon visions of desert and barrio, shantytown and wilderness sunrise. This imagined universe is both city of blinding lights and abandoned vista, a new Jerusalem and a rural jubilee, a radical Rivendell and a river rolling down a mountain, a liberated

Based on what I call Blake’s “biblical utopianism,” a notion that echoes “thy kingdom come on earth as it is heaven, ” I believe “Streets” is a call, ultimately, for a classless and borderless transcendence of race, class, and gender divisions. As in other songs, Bono reiterates his recurring theme for economic revolution, egalitarian revival, and ecumenical revelation.

Like William Blake before him, Bono believes in a lyrical cosmos where all things are always already simultaneously spiritual and political. So, the nameless streets signify inner and outer liberation. Thus, what Christopher Hobson asserts about Blake’s visionary poetry applies here: “If there is continual forgiveness of sin, the ideological justification for a hierarchy of social guardians vanishes, a crucial step in convincing people to abolish the hierarchies in reality.”

Clearly, on the current Vertigo tour, Bono brings this aspect of the “Streets” idea to center stage as a rhetorical device advocating the eradication of poverty and the invocation of equality. During what’s come to be known as the “Africa Section” of the show, Bono preaches in an inspired oration that echoes Dr. King, “From the swamplands of

This sense of universal humanity in the likeness of the creator comes cloaked in rock and roll idioms and traverses to a mountaintop beyond ideology. And in its universalist wisdom, this place is every place the listener pictures it to be, whether a biblical Eden/Heaven/New Jerusalem or a secular someplace of economic equality.

While I want to run, I’m no longer willing to hide. Breaking down all borders and walls inside, this hunger for justice is something to shout about. I want the dust cloud of domination to disappear without a trace.

I want to touch this flame in our lifetime, even with those listeners who have commented that this song is singularly about heaven, about the Christian idea of an afterlife. Because like Blake, Bono’s is an “ethical, common-people’s Christianity of tolerance and forgiveness,” we need not wait for the great beyond to become agents of solidarity and justice, hospitality and humility, mercy and meaning.

What would that world look like if we lived where the streets have no name? For the present of Bono’s post-political humanitarianism, it looks like King’s notion of a beloved community beyond the excesses of neoconservative capitalism and the human rights’ errors of old school state communism. For me, it’s clearly a cooperative and antiauthoritarian world based not just on my reading of Blake, Bono, and the bible—but on all this and so much more. Beaten and blown by the winds of cynicism, we can still burn down the old world of narrow-minded oligarchies and build the new one based on love.